At this moment there are photos of 39 of the approximately 72 species of Dutch dragonflies and damselflies on my website. So I still have quite a few on my wish list. Some I will probably never get in front of my camera, such as the golden-ringed dragonfly (Cordulegaster boltonii). This is, with a length of 8.5 cm, the largest dragonfly in our country. That’s just one millimetre longer than the blue emperor (Anax imperator). The golden-ringed dragonfly is a very rare species. It only occurs in a few places in the province of Limburg, in the southernmost part of the Netherlands. It is not just due to the rarity that some species are missing in my overview, because I do have photos of a number of other rare species. One of them stands head and shoulders above the rest in my opinion. I think it is one of the most beautiful dragonflies in our country. It is not without reason that I have this species in my logo: the banded darter (Sympetrum pedemontanum).

No mistake possible

With dragonflies, mistakes can sometimes arise as to which species it is. Among the dragonflies there are plenty that are greenish and blueish and that can look very similar at first sight. The same applies to the damselflies, especially the species with a partially blue abdomen, such as the azure damselfly (Coenagrion puella), common blue damselfly (Enallagma cyathigerum) and variable damselfly (Coenagrion pulchellum). To help you tell these blue damselflies apart, the Dutch Butterfly Foundation has made a recognition card. Even then a mistake is easily made. In the case of the banded darter, however, a mistake with another species is impossible, at least in the Netherlands. This dragonfly is characterised by a dark brown band across the wings. There is no other dragonfly species in Northwest Europe that has this. In addition, they have fairly large pterostigmata (the spots at the wing leading edge). In this case, they are red in the males and cream in the females.

Smallest darter

When the male banded darter has reached maturity, it has a beautiful red abdomen, similar to the ruddy darter (Sympetrum sanguineum). And if you don’t see the wings, you could just mistake it for this species. It is not surprising, of course, because they belong to the same genus of dragonflies (Sympetrum). The banded darter, together with the black darter (Sympetrum danae) and the very rare spotted darter (Sympetrum depressiusculum), is the smallest of the darters in our country. As often happens with dragonflies, the young males resemble the females with their yellow abdomen. As mentioned before, mature males have a red abdomen. Mature females have a brown abdomen.

Seepage

The banded darter feels completely at home in shallow, slowly flowing waters, for example streams and ditches as well as stagnant waters, puddles and swamps, especially when these are sun-exposed. Banded darters also have a preference for water where seepage is present. Seepage, in short, is groundwater that comes to the surface. It is usually very low in nutrients and oxygen and often also high in calcium and iron. The latter ensures that places where seepage water comes to the surface (the so-called seepage point) often has a specific rust-brown colour. This is because the dissolved iron oxidises with the oxygen from the air to iron oxides, i.e. rust. These iron oxides are not soluble in water and will therefore precipitate as a solid. In addition, the iron in seepage can also bind to phosphates. These chemical substances are often present in the water from manure or artificial fertiliser. Then iron phosphates are formed, which results in a thin blue to purple film on the water. Actually, it is not the iron phosphates that float on the water, but millions of iron-loving bacteria that feast on the iron phosphates. You’ve probably seen it. It looks like a film of oil floating on the water. The difference between such an iron phosphate film and an oil film is easy to check. If you poke the film with a stick or throw a stone into it, the iron phosphate membrane will break open and stay that way. If the membrane immediately closes again, you are dealing with oil contamination. Then contact the water board, because we obviously do not want oil in the water.

From the Netherlands to Japan

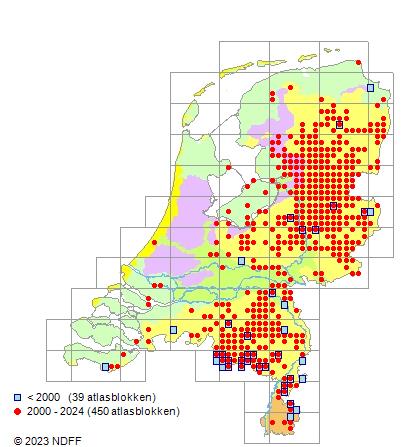

(Bron: NDFF)

The banded darter has a large distribution area from Western Europe to Japan. The western border of the distribution area cuts vertically through the Netherlands, Belgium and France. This species can usually not be found south of the Alps, although there are some small, isolated populations here and there in Spain, Romania and the Balkans. In Great Britain the banded darter is completely absent. Only once did Ian D. Smith by accident find a strayed specimen in South Wales, on August 16 and 17, 1995. The nearest population of the banded darter at that moment was in the southeast of the Netherlands. Ian wrote a very interesting article about this find which you can read at the website of the British Dragonfly Society. The dragonfly did not occur in the Netherlands until the eighties of the last century. In the last two decades of the 20th century, they were observed in dribs and drabs in the province of Limburg and in the southeastern part of the province of Brabant. Since 1999, the species has become more common and has now spread across the east of the country. In the province of Overijssel the chance of finding them is the greatest.

Fly out at the same time

The banded darter flies from mid-June to early September, with a peak in late July and early August. After mating, the eggs are deposited by the female. First, the male holds the female firmly in tandem position during egg deposition. But as soon as he sees that everything is going well, he releases the female and she continues alone. It does this in flight in places with many aquatic plants. The eggs are, as it were, laid on the surface of the water. She therefore hardly dips her abdomen in the water, as you see with other species of dragonflies. The eggs overwinter and then hatch in spring. The banded darter therefore has a one-year cycle. There is not, as in other species, one or more hibernations of the larvae. The banded darter larvae then develop very quickly and emerge from mid-June. In some cases, this emerging takes place in a very short period of time, which means that a lot of fresh imagines can suddenly be flying around at a location.

But that’s not a punishment in case of a banded darter, is it?

Sources:

- Dutch Butterfly Foundation

- Wikipedia (banded darter)

- Wikipedia (seepage)

- British Dragonfly Society (observation of a banded darter in Wales in 1995)

This blog was originally published in Dutch on March 11th 2023